MissionLiFE

October 15, 2024

[ad_1]

1. Introduction

Climate change has increasingly strong and long-lasting impacts on people’s lives [1]. Both direct exposure to climate change, whether acute (e.g., extreme weather, wildfire) or chronic (e.g., heat, drought, decreased air quality), as well as indirect exposure (i.e., the idea or social representation of climate change) have been found to be associated with decreased well-being and negative physical and mental health outcomes [2,3,4].

Worry about

climate change includes both

micro-climate worry, which entails worrying about negative consequences for oneself or one’s family/friends, and

macro-climate worry, which entails worrying about negative consequences for animals and plants, people in poorer countries, or future generations [4]. Indeed, according to the Office for National Statistics in Great Britain [5] around three in four adults (74%) reported feeling (very or somewhat) worried about

climate change in Great Britain. Similarly, Hickman and colleagues [6] revealed in their study across 10 countries (Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the UK, and the US; 1000 participants per country) that 59% were very or extremely worried, and 84% were at least moderately worried about climate change.

Worry about climate change is a complex environmental emotion that can have contrasting effects—negatively impacting mental health while simultaneously encouraging behavioral engagement. Specifically, worry about climate change has been found to be associated with greater depression, anxiety, and stress, impacting the mental health of young Italian adults [7]. Similarly, these researchers reported a positive effect of climate change worry on future anxiety, suggesting that concerns about the climate crisis reinforce a negative and anxious outlook toward the future in young Italian adults [7]. The negative association between worry about climate change and mental well-being was also found in data collected from multiple European countries and Israel [8] and in a study of Norwegian adolescents, which demonstrated a significant association between climate change worry and depressive symptoms, lower subjective well-being, and reduced expectations of experiencing happiness in the future [9]. Nevertheless, a previous study revealed that the more individuals worried about climate change, the stronger their feelings of personal responsibility to reduce it, which, in turn, was linked to support for climate policies and personal climate mitigation behaviors [10]. Likewise, in a study which used data from 23 countries that participated in the European Social Survey Round 8 (N = 44,387), worry about climate change was an important predictor of individuals engaging in both energy curtailment and energy efficiency behaviors [11]. In line with this, worries about climate change appear to play a pivotal role in one’s subjective well-being and behavioral engagement [12].

Such feelings of worry might change during armed conflicts, as armed conflicts compound immediate feelings of fear and uncertainty [13,14], whereas climate change is perceived as a future and psychologically distant threat [15]. Nevertheless, there is a reciprocal relationship between climate change and armed conflicts. Specifically, armed conflicts contribute significantly to environmental degradation and climate change, as military activities and conflicts lead to deforestation, soil degradation, and increased greenhouse gas emissions, further accelerating climate change [16]. Moreover, destroying infrastructure and displacing populations during conflicts can result in significant environmental damage, disrupting ecosystems and increasing vulnerability to

climate impacts [17]. Conversely, climate change can contribute to armed conflict by intensifying resource scarcity and sociopolitical tensions, particularly in regions with high population densities and low adaptive capacities [18,19]. Thus, we hypothesized that during an armed conflict, participants would report lower levels of climate change worry.

Given the aforementioned vicious cycle that poses significant challenges to global security and environmental sustainability, the focus of the current study was on climate change worry during an armed conflict in Israel. On 7 October 2023, Hamas terrorists in Gaza fired thousands of rockets toward Israel [20], and since then Hezbollah (a terrorist group situated on Israel’s northern border) has continuously sparked daily bushfires in northern Israel (a result of their own rocket attacks on

Israel), with swathes of forest reserve destroyed and people hospitalized for smoke inhalation [21]. In this context, we aimed to explore whether climate change worry might have decreased and whether climate change-related factors might explain this worry differently as a result of the armed conflict.

The theoretical framework that guided the present study was the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TTSC) [22], which focuses on the interaction between individuals and their environment. According to the TTSC, individual appraisal processes are composed of evaluating the stressors’ relevance (primary appraisal) and the individuals’ resources to overcome these stressors (secondary appraisal), with both appraisals highly influencing stress responses. Primary and secondary appraisals are believed to impact the coping strategies chosen by individuals. These processes are dynamic and interrelated, as individuals continually appraise changes in the situation and their ability to cope [22]. Thus, in the present study, we also examined the interplay of risk appraisal related to climate change, pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs), and climate change worry before and during an armed conflict in Israel.

Risk appraisal related to climate change (hereafter, risk appraisal) involves evaluating the likelihood and severity of climate change impacts [23]. A previous study revealed that higher

risk appraisal was associated with increased stress, as individuals perceived greater threats to their well-being [24]. In addition, risk appraisal has been found to be positively associated with climate change worry among adult participants [25]. In line with this notion, we hypothesized that during an armed conflict, participants will report lower levels of risk appraisal, and that the association between risk appraisal and climate change worry will be weaker during the armed conflict than during a period of peace.

Pro-environmental behaviors are defined as purposeful actions that can reduce negative environmental impacts via three major behaviors: waste reduction, reuse, and recycling [26]. According to Helm and colleagues [27], “PEBs can best be described as a mixture of self-interest (e.g., changing behavior to minimize one’s own health risk), and of concern for other people, future generations, other species, or whole ecosystems (e.g., preventing air pollution that may cause

climate change)” (p. 161). Scholars have revealed a consistent positive association between PEBs and well-being or

life satisfaction [28,29]. Additionally, engagement in PEBs has been found to be positively associated with climate change worry [30]. Based on these previous findings, we hypothesized that during an armed conflict, participants will report lower levels of engagement in PEBs, and that the association between PEBs and climate change worry will be weaker during the armed conflict than during a period of peace.

In reference to the association between risk appraisal and PEBs, it was found that risk appraisal promoted

mitigation and adaptation behaviors and significantly impacted stress levels [27]. Thus, in the present study, the mediating role of PEBs was assessed within the direct link between risk appraisal and climate change worry. We hypothesized that a greater decline in risk appraisal will be associated with a greater decline in PEBs, which will subsequently be associated with a greater decline in climate change worry.

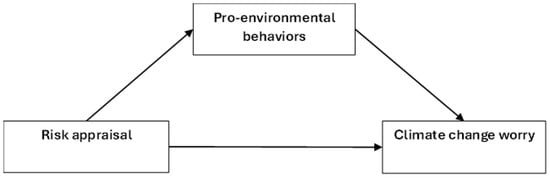

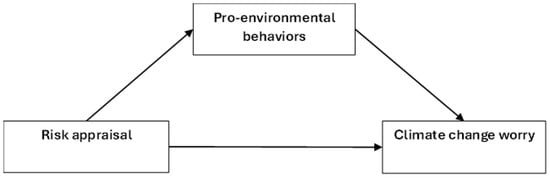

Taken together, in the present study, we examined the following: (a) differences in climate change worry (outcome variable), risk appraisal, and PEBs before and during an armed conflict; (b) differences in the direct associations between the independent variables (i.e., risk appraisal and PEBs) and climate change worry before and during an armed conflict; and (c) the indirect effect of PEBs (mediation effect) in the association between risk appraisal and climate change worry before and during an armed conflict (See Figure 1).

3. Results

About a third of the participants (n = 66, 32.7%) reported at least one experience related to the armed conflict: loss of a family member, acquaintance, or close friend (n = 39, 19.3%); injury of a family member, acquaintance, or close friend (n = 39, 19.3%); being close to a hostage (n = 19, 9.4%); or being evacuated from home (n = 10, 5.0%). The experience of the armed conflict was not related to the study variables at Time 2 (p = 0.056 to p = 0.590). The participants’ ages were associated with PEBs at both times (Time 1: r = 0.15, p = 0.028, Time 2: r = 0.16, p = 0.027), and income level was associated with climate change worry at Time 2 (r = 0.20, p = 0.004). Men reported higher PEBs at Time 2 than did women (mean = 2.70, SD = 0.75, vs. mean = 2.47, SD = 0.80; t (200) = 2.04, p = 0.021). Thus, age, gender, and income level were controlled for in further analyses.

A comparison of the study variables by time (Table 2) showed a significant decline in both climate change worry and risk appraisal. No change was found for PEBs. Thus, the hypotheses that the levels of climate change worry and risk appraisal would decline during an armed conflict were supported but not the hypothesis for PEBs.

The direct associations between risk appraisal, PEBs, and climate change worry were examined with Pearson correlations (Table 3). All associations were positive and significant, revealing that a higher risk appraisal was associated with higher PEBs, and both were associated with higher climate change worry, at both times. No differences were found in the extent of the associations between the two times (risk appraisal and worry: t (213.28) = 0.07, p = 0.948; PEBs and worry: t (212.58) = 0.06, p = 0.948; risk appraisal and PEBs: t (222.93) = −0.85, p = 0.396). Thus, the hypotheses related to the associations between risk appraisal and climate change worry, and between PEBs and climate change worry, were not supported.

The study model was examined with the PROCESS procedure, model 4 for mediation [38]. The model was first examined for the first measurement, and then for the change scores. Before conducting the PROCESS analysis, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were calculated for each variable to assess potential multicollinearity (multicollinearity defined as VIF > 10) [43]. The highest VIF value for the Time 1 model was 1.13, and for the change scores model, it was 1.11. The Durbin–Watson test yielded a value of 2.07 for the Time 1 model and 1.89 for the change scores model. In both cases, the scatterplot showed widespread points, indicating that the data were homoscedastic.

The indirect effect for Time 1 was significant (effect = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.03, 0.13), revealing that a higher risk appraisal was associated with higher PEBs, which in turn was associated with higher climate change worry (Figure 2).

However, as both the indirect and the total effects were significant, the association was partly direct and partly mediated. The mediated proportion was found to be 13.5%, and thus most of the association was direct.

Finally, the study model was examined for the change scores. The indirect effect for the change scores was significant (effect = 0.07, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.02, 0.13), revealing that a greater decline in risk appraisal was associated with a greater decline in PEBs, which in turn was associated with a greater decline in climate change worry (Figure 3).

As before, the association between change in risk appraisal and change in climate change worry was partly direct and partly mediated. The mediated proportion was found to be 19%, and thus most of the association was direct. The hypothesis related to the mediation effect was thus supported, although the indirect effect was partial.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we investigated how climate change worry, PEBs, and risk appraisal were affected post-October 7th, during the 2023 Swords of Iron War in Israel. Drawing on the TTSC [22], we aimed to understand whether immediate threats such as an armed conflict would diminish concerns about long-term stressors such as climate change. Previous research has highlighted how conflicts can dominate psychological resources and influence environmental concerns [16]. The current study provides insights into the shifts in climate-related worries and behaviors during times of crisis. Our findings are consistent with previous research, which has shown that immediate threats, such as the physical and emotional dangers associated with armed conflicts, can overshadow future-oriented worries such as those about climate change [13,14]. This finding aligns with the TTSC [22], which posits that immediate stressors tend to take priority in individuals’ cognitive processes. Armed conflicts present an urgent and tangible risk that may prompt individuals to shift their mental resources toward more immediate concerns, relegating long-term threats, such as climate change, to a lower level of awareness. Additionally, the literature suggests that climate change is often viewed as a psychologically distant phenomenon [15], a notion that might further explain why individuals in the current study focused less on climate change during the conflict.

According to the findings, there was no significant change in PEBs before vs. during the armed conflict, which runs counter to the expectation that engagement in these behaviors would decrease due to the overshadowing effects of the conflict. The lack of significant change in PEBs suggests that once established, PEBs may persist, even during crises. This resilience in behavior might reflect a habituated response, where individuals continue to act pro-environmentally even when their cognitive focus shifts away from long-term environmental risks. These findings align with prior research showing that PEBs are often driven by a mixture of self-interest and concern for others [27]. It may be that PEBs are not solely linked to an individual’s worry about climate change but also to a more stable ethical or personal commitment to environmentalism [26]. The persistence of PEBs highlights the need to support and encourage these behaviors as habitual practices, which are resilient even in the face of external stressors such as armed conflicts.

The decline in risk appraisal during the armed conflict reveals that participants perceived climate change as a less immediate threat when being confronted with more direct, pressing concerns. This decrease indicates that individuals may psychologically distance themselves from longer-term threats, such as climate change, when more immediate risks, such as those posed by war, are present [24]. From the perspective of TTSC [22], the focus of the primary appraisal during a war would be on survival and immediate safety, shifting attention away from secondary stressors such as environmental concerns. This notion is supported by research on the effects of armed conflicts, which has shown that

mental health and cognitive resources are often strained under conditions of acute stress [13]. However, this reduced risk appraisal has long-term consequences for environmental policy, as it underscores the challenge of maintaining environmental risk awareness during crises.

The mediation analysis revealed that PEBs partially mediated the relationship between risk appraisal and climate change worry. A significant indirect effect was found, meaning that the decline in risk appraisal led to a decline in PEBs, which in turn contributed to a decline in climate change worry. However, the mediation effect was partial, indicating that most of the association between risk appraisal and climate change worry remained direct. This finding supports the idea that engagement in PEBs can influence emotional responses to environmental threats [27]. Prior studies have shown that individuals who engage in PEBs tend to report lower levels of environmental stress, possibly because they feel more empowered and in control of their contribution to mitigating climate change [28]. However, as the mediation effect was partial, it seems that risk appraisal played a strong direct role in shaping climate change worry.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, the study sample was drawn from an online panel, which may not fully represent the broader Israeli population. Participants who engage in online surveys might have different levels of environmental concern or conflict exposure compared to those who do not participate in such panels. Thus, generalizing the findings should be conducted cautiously. Second, all data were collected through self-reported measures, which can introduce biases such as social desirability bias or recall bias. Third, related to the previous points, a larger sample size would have allowed the use of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), enabling the inclusion of latent variables and multigroup analysis based on time (Time 1, Time 2). Fourth, the study’s two time-points, although strategically chosen, may not have captured the full temporal dynamics of how climate change worry fluctuates during and after armed conflicts. Future studies might benefit from additional time-points to allow for a better understanding of the long-term effects of armed conflicts on environmental concerns. Fourth, the study was conducted in Israel during a specific armed conflict, thus potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other regions or conflicts. Different cultural, political, and environmental contexts may yield different results, suggesting that other scholars replicate the present study model. Fifth, the study did not account for all possible confounding variables, such as participants’ previous experiences with climate change or their political views, which may have influenced both their climate change worry and their responses to armed conflict. Finally, a specific set of PEBs was measured, which may not have encompassed all types of environmental actions relevant to different individuals. This aspect may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader environmental engagement.

4.2. Implications

The findings of this study offer practical implications for maintaining environmental engagement during times of crisis. The decline in climate change worry and risk appraisal during an armed conflict suggests that immediate threats overshadow long-term concerns. Policymakers and environmental organizations should develop strategies to keep climate change awareness front and center, even amidst conflict, ensuring that public awareness does not wane. Doing so could involve targeted communication campaigns that acknowledge immediate stressors while emphasizing the continued importance of environmental sustainability. Furthermore, the resilience of PEBs observed in the study highlights the value of fostering habitual behaviors that can persist despite external stress. Programs that encourage these behaviors as routine actions could help ensure that individuals remain engaged in environmentally positive practices, even during crises. Mental health professionals might also play a role in integrating environmental concerns into broader well-being interventions during periods of conflict, addressing both immediate and long-term challenges.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

[ad_2]

Source link

Related

Discover more from Mission LiFE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.